Until 30 March 2024, our federal government is taking public submissions on its proposed reforms to Australia's environment law – the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act 1999.

In this guide – which you can read below or download as a PDF – we’ve outlined EJA’s key concerns with the proposed reforms, and what needs to change to make sure our new laws actually protect our environment and reverse our extinction crises.

This is the latest stage of consultation in a once in a generation reform process.

You can have your say on the proposed changes to our environmental laws until 30 March 2024.

Ready to make a submission?

Scroll down for a step-by-step guide

To read the concerns and recommendations of EJA lawyers, scroll down to read the full submission guide or download a PDF version.

Then, also email your submission directly to

- Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek

- your local federal MP

WHY THIS MATTERS

It's time for environment laws that actually protect the environment

Australia’s new generation of environment laws need to end the death-by-a-thousand-cuts crisis our environment is facing.

Australia is a global deforestation hotspot with an alarming rate of wildlife extinction, rampant lawless land clearing and escalating climate change.

Overhauling the nation’s environment laws only happens once in a generation – so we have to get this right.

Good laws, properly used, are key to halting the destruction, reversing the decline, and bringing nature back.

But the proposed laws are not yet rigorous enough to get us there – and at worse, will take things backwards.

Getting started

You can either:

- Lodge your submission online through the federal government’s consultation hub: https://consult.dcceew.gov.au/australias-new-nature-positive-laws, OR

- Email your submission to [email protected]

In addition, we recommend you email your submission directly to

- Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek at [email protected], and

- your local federal MP.

You must lodge your submission by Saturday, 30 March 2024.

If you lodge your submission via the consultation portal, you can provide your comments either by entering them in the text box on the survey page, or by uploading a submission as a PDF on the following page.

If you want to write a longer submission, we recommend you draft your comments in a Word document or text editor.

Once you have finished, click through to the final page and click "Submit to lodge your comments."

If you have any questions, need additional support or want to share your submission with us, get in touch at [email protected].

How to structure your submission

The best submissions are unique. Good submission generally:

- Are concise and well-structured

- Emphasise the key points so they are clear

- Outline concerns as well as suggesting recommendations to address them

- Only include information and documents that are directly relevant to your key points.

- Only include information you are comfortable to see published on the internet.

Begin your submission by briefly introducing yourself or the group or organisation you represent.

- You can include basic information like your name and where you live.

- Are you from an group or organisation whose work is relevant to protecting the environment?

Once you have introduced yourself, move on to sharing why this issue is important enough to you for you to spend time writing a submission to the Federal Parliament.

- Are you concerned about a particular animal, plant, or ecosystem?

- Is there something you feel particularly strongly should be addressed in the reforms?

- Have you experienced or witnessed the impacts of environmental harm?

a. Outline your concerns

Summarise your key concerns. Are the draft laws good enough? Why, or why not? What are your key concerns?

You can refer to the information we have included below to do this.

b. Provide suggestions

Summarise what you think needs to change to address your concerns. You can refer to the information below to help you with this, too.

You can include as much, or as little, information as you would like.

You can comment on all of the issue areas listed on the submission portal, or just the ones you are most interested in.

If you are particularly interested in a specific area or areas of environmental protection, you may like to do additional research and include your own information in your submission.

Once you have written your submission, save the Word document onto your computer.

You can return to the submission portal to complete your submission, or attach it to an email and send it to [email protected].

If you submit via the government portal, follow the steps below to navigate the survey form.

- On the consultation page, scroll to the bottom and click Start survey.

- The survey will ask you to answer three questions and indicate what topic area you are making a submission on.

- You can choose to address one topic, or as many topics as you like.

- You can provide your comments either by entering them in the text box on the survey page, or by uploading a submission as a PDF on the following page.

- Once you have finished, click through to the final page and click Submit to lodge your comments.

Once you've sent your submission, we recommend you also email it directly to Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek at [email protected] and to your local federal MP.

We recommend you also email your submission directly to:

- Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek at [email protected]

- and to your local federal MP.

A quick summary of EJA's key concerns and recommendations

To meet the federal government’s commitment to end deforestation by 2030, our new laws must include much stronger protections for native forests. Land clearing – which currently escapes federal assessment time and time again – must be clearly brought within the new laws.

We need a land-clearing trigger – either in the new Act or in the new National Standard for Threatened Species and Communities. This will ensure plans to clear areas over a certain size where threatened species are likely, or may occur, must be assessed under the new laws.

Read more about Matters of National Environmental Significance

The federal government has promised to turn around the extinction crisis and protect critical habitat, but the draft laws remove legal protections available for critical habitat in favour of narrower, ambiguous new terms like “irreplaceable.”

Our new laws need to strengthen protection for critical habitat and make it mandatory for every species. This will ensure species like the koala don’t become extinct – one of hundreds of Australian species on the path to extinction because of habitat destruction. Red-lines to protect critical habitat must be drawn for every species.

The draft laws do not mention halting the decline of threatened species.

To deliver on its promise of no new extinctions, the federal government must introduce laws that rule out impacts that reduce the population numbers of species that are already on the path to extinction.

This requirement must be a centrepiece of the new National Standard for Threatened Species and Communities.

Nothing that pushes threatened animals and plants closer to extinction should be permitted. Halting and reversing decline should be a stated purpose of the new Act.

Climate change exacerbates all of the pressures our environment is already facing, and widespread and severe climate impacts are already being felt across the continent. Our new laws must include a new climate ‘trigger’ to specifically require proper assessment of projects that will create significant carbon emissions (100,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent), and ensure projects with unacceptable climate risks cannot proceed.

To be effective, a climate trigger must include emissions that will result from Australian gas and coal being burnt overseas (scope 3 emissions). Our new laws must also respond to escalating climate impacts and protect ecosystems that absorb carbon.

Environmental decision making must be based on the best available science and clear rules – no loopholes or special deals – not the personal whim of the decision maker of the day. Our new laws must remove excessive decision-maker discretion.

For example, it’s proposed that decisions about whether impacts are unacceptable and comply with the new National Standards will be subjective decisions that “satisfy'' the EPA; instead, these decisions must reflect the science.

Communities must have the right to review the merits of decisions – to make sure they properly follow the science.

There should be no Ministerial call-in powers that allow the Minister of the day to override the EPA and make political decisions to approve environmental destruction.

And, we need an EPA set up to succeed. To genuinely safeguard this powerful new position from political interference, the EPA CEO must be accountable to an independent board with qualified members.

Read more about the new Environment Protection Agency and assessments and approvals

Too often, offsets look good on paper but in practice they let companies off the hook for destroying and polluting our environment. Few gains are ever made on the ground from planned offset activities, which are supposed to make up for real-world losses suffered by species from destructive practices.

No one should be able to buy the right to kill threatened species or bulldoze their habitat; introducing this proposal will take our environment laws backwards not forwards.

Our new laws must include strict rules on offset activities to make sure they actually deliver on-ground results for the same species in meaningful time frames.

Red-lines need to be set that won't allow offsets for everything – for species already on the path to extinction, critical habitat and population losses cannot be offset.

And, the government must rule out payments for destruction.

EJA's full submission guide

If you make a submission using the online portal, open the government's online portal and click "start survey" to begin.

A survey will ask you to answer three questions and indicate what topic area you are making a submission on.

You can choose to address one topic, or as many topics as you like.

The topics are:

- Matters of National Environmental Significance

- National Environmental Standards

- Climate change

- Community engagement

- Conservation planning

- Environment Information Australia

- Environment Protection Australia

- Environmental assessments and approvals

- Regional planning or strategic assessments

- Other

Scroll down for the key concerns and recommendations from EJA lawyers on each of these topics – or download the guide as a pdf.

1. Matters of National Environmental Significance

Key points

Australia’s new environment laws must properly protect Matters of National Environmental Significance:

- Some plants, animals, places and potential impacts are so important, they are listed as nationally significant. Our new laws need to increase their protection – not make it optional.

- Protections for nationally significant matters already listed cannot go backwards. This means Australia’s new laws must continue to protect species considered ‘extinct in the wild,’ and continue to protect the environment from nuclear actions.

- We need new nationally significant matters on the list to meet the climate and extinction crises we now face, and bring our laws into the 21st century.

- A land clearing trigger and a climate trigger must be introduced to properly address the deforestation and climate crises in Australia.

More detail

Matters of National Environmental Significance (MNES) are plants, wildlife, places and certain actions explicitly protected under our national environmental laws (also known as ‘Protected Matters’).

More than 2100 plants, animals and ecological communities are protected under Australia's national environment laws as MNES.

Current protections cannot go backwards

Environmental lawyers believe Australia’s new environment laws must retain two key safeguards for all nationally protected plans, wildlife and places.

Species at risk of extinction are protected as Matters of National Environmental Significance. If a species is considered extinct in the wild, it is still considered a MNES.

Proposed changes to our laws would remove species extinct in the wild from MNES protection. This change is a huge step backwards in protecting nature. Our new environment laws must maintain the definition of MNES to include species extinct in the wild.

This is to ensure if an extinct animal or plant is re-discovered in the wild, it will be protected automatically without requiring a separate process which might be too slow, bureaucratic and ineffective to deal with any urgent threats.

The draft reforms also propose a change to how nuclear actions are defined. Our current laws include a nuclear action trigger, which is intended to protect the environment – particularly MNES – from impacts of nuclear actions.

The proposed reforms will narrow this definition to ‘radiological impacts’.

Our new laws cannot go backwards in protecting our environment from the harms of nuclear projects. The nuclear action trigger must be retained as it is in any new environment laws.

New nationally significant matters should trigger protection:

Additionally, three new triggers for assessment must be included in our new environment laws. Triggers are identified thresholds or actions requiring assessment for their potential environmental harm.

A land clearing trigger must be introduced to address the enormous failure of our current laws to address the land clearing crisis in Australia.

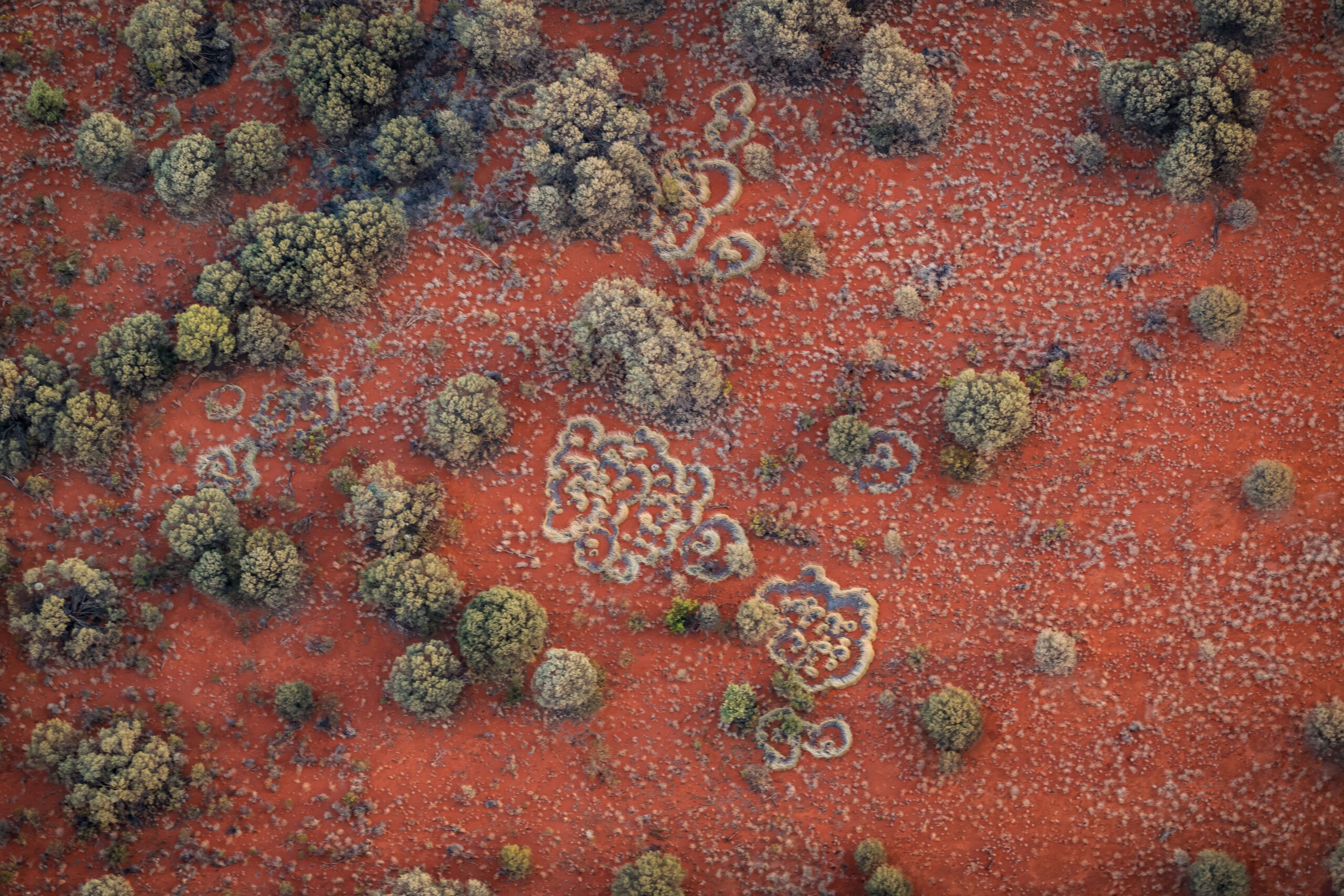

Not only is Australia a global deforestation hotspot alongside Brazil and Borneo – almost no land clearing is even assessed for environmental impacts, let alone approved, under our current national environment law. But land clearing is happening daily in areas mapped by the federal government as likely to contain listed threatened species.

Our current environment laws have failed to address the land clearing crisis in Australia. The new laws cannot let this go on. Land clearing must trigger an assessment and require approval under the new Act – just like every other sector that may, or is likely to, significantly impact listed threatened species.

Introducing a land clearing trigger would ensure any plan to clear land over a certain size in areas that may contain, or are likely to contain, listed threatened species requires federal government assessment and approval. The trigger could sit in the Act as a new section, or as a statement in the new National Environmental Standard for Threatened Species and Ecological Communities.

In Queensland, more than 2.1 million hectares out of 2.2 million hectares cleared between 2016-2021 was within areas mapped by the Federal Government as likely to contain threatened species. Yet almost no federal assessments of environmental impacts took place, nor any Federal approvals, for this mass-scale deforestation devastating habitat for our wildlife on the path to extinction.

For our iconic and beloved koalas, more than 730,000 hectares of habitat mapped as likely to contain koalas was cleared in Queensland between 2016-2021. Koalas are now listed as Endangered, with habitat loss a primary threat – yet land clearing of koala habitat still does not undergo federal environmental assessment or approval.

A land-clearing trigger is a simple solution to help end the deforestation crisis in Australia – and put us on track to meet Australia’s commitment at the COP26 climate summit in 2021 to end deforestation by 2030. This trigger will make sure land clearing complies with the same restrictions as any other sector – it must have environmental impacts assessed, it cannot have unacceptable impacts, and it must comply with the new National Environmental Standards, to protect threatened plants, wildlife, and ecosystems.

A climate change trigger must be introduced.

Widespread and severe impacts from climate change on ecosystems and wildlife are already being felt across Australia. Despite this, the current draft laws do not require projects creating high levels of climate pollution (like new coal and gas projects) to be assessed for their climate impact on our environment.

A new mechanism must be included to enable the proper assessment, and prevention, of new polluting projects on the basis of their carbon emissions.

This trigger should apply to any project with emissions over the threshold of 100,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent, including Scope 3 emissions.

This will ensure the climate impacts of a project are specifically addressed when a decision maker is considering whether to approve a project.

Just like individual species, ecological communities listed as ‘vulnerable’ should be a Matter of National Environmental Significance.

Currently, ecological communities are only considered Matters of National Environmental Significance if they are listed as Endangered or Critically Endangered. For individual species, like a plant or animal, this protection extends to those listed as Vulnerable to extinction.

In our new laws, ecological communities listed as Vulnerable must also be protected. This will ensure impacts on vulnerable ecosystems are assessed and protections apply to them, such as prohibitions on unacceptable impacts and requirements to comply with the National Environmental Standards.

This is to recognise the fundamentally interconnected nature of our environment – especially so for ecological communities, which comprise unique native plants, animals and organisms

2. National Environmental Standards

Key points

To make our new laws effective and fair, Australia’s new National Environmental Standards must:

- Rule out impacts that cause declines in population numbers of threatened species.

- Rule out destruction of habitat critical to survival of threatened species.

- Include requirements to maintain and improve both habitat and population numbers of threatened species.

- Not allow payments that permit the destruction of listed threatened species and ecological communities – called ‘restoration contributions.’

- Be clear, specific, measurable and outcome-focused – not vague and high-level.

More detail

One of the most important recommendations from the independent review of the EPBC Act is to establish a rules-based system that requires compliance with clear rules and outcomes for our environment, especially threatened species.

This recommendation seeks to transform our environment laws from a system based on discretion and political decisions, to a system based on clear rules: red-lines that can't be crossed for our environment.

The new National Environmental Standards have the potential to turn the tables in favour of our threatened species – taking us from decline to recovery. Under the reformed laws, all projects will have to comply with the Standards.

There will be a number of different National Environmental Standards, each addressing a particular topic, like threatened species and ecological communities, environmental information and data, and community consultation.

Clear and specific Standards for Threatened Species and Communities were the centrepiece of the independent review of our national environment laws.

But the draft Standards now proposed by government are too weak and high-level to be effective. They use brief, high-level language, fail to set out clear rules, and offer little on-ground protection.

To make a difference on the ground for our environment, all the National Environmental Standards must be clear, specific and outcome focused. They need to explicitly prohibit specific impacts on threatened species habitat and populations, and set out the outcomes for threatened species that projects must be consistent with.

The new Standards for Threatened Species and Communities should better reflect what was recommended in the Samuel review, and at minimum must include:

- Clear requirements to maintain and improve both habitat and population numbers of threatened species and ecological communities.

- Rule out impacts that cause declines in population numbers of threatened species, or adverse impacts to habitat critical to the survival of threatened species.

- A requirement to be consistent with threat mitigation statements, and not exacerbate key threats, including any threats identified in Recovery Strategies, listed threatening processes and threat mitigation statements.

- A standard – of enhancing the conservation status of any impacted matter of national environmental significance, and ensuring recovery occurs over biologically meaningful timeframes, by halting and reversing trajectories of decline for threatened species and ecological communities.

- Any requirement for “net positive outcome” should be clearly required for each individual affected threatened species or ecological community – rather than an ‘overall goal’ that allows trade-offs between species – inevitably causing further decline.

3. Climate change

Key points

Our new laws must put the impacts of climate change on our environment front and centre and:

- Explicitly require assessment of climate risk, with the power to reject projects due to their likely climate impacts.

- Ensure assessment of all projects includes all climate emissions (scope 1, 2 and 3) in environmental impact assessments, and take account of cumulative impacts.

- Increase protections for ecosystems that absorb carbon.

- Ensure climate change considerations are incorporated at every stage.

More detail

Climate change threatens every ecosystem across the continent and widespread and severe effects are already being felt by vulnerable and iconic wildlife.

Yet right now, the draft laws do not require decision makers to properly scrutinise the climate risk of proposed projects.

Australia’s new laws should clearly mandate scrutiny of the climate risk of proposed projects (including all new coal and gas projects) and have the power to reject them due to their likely impacts.

Project assessment should have to consider the total, cumulative climate impacts of a project (or group of related projects), including emissions resulting from Australian gas and coal being burnt overseas (scope 3 emissions).

If our laws ignore the climate pollution from the coal and gas we export, this means Australia is not taking responsibility for the devastating climate impact these downstream emissions will have globally and right across the Australian environment.

4. Community engagement

Key points

Australia’s new environment laws must give communities legal rights:

- To access information.

- To participate meaningfully and be heard in environmental decision-making processes overseen by the new national EPA.

- To seek independent review of the merits of decisions.

More detail

Under our current laws, requirements for community participation leave a lot to be desired.

Consultation is a tick-box exercise.

It often looks like a bit of information posted on a hard-to-navigate website, and a quietly advertised opportunity to comment within a short consultation window.

Australia's new laws must fix this.

They must include clear requirements, in line with established best practice, for public participation in environmental decision making – at every stage of the process.

Consultation at every stage

Thorough community consultation should be undertaken by the new national Environment Protection Australia (EPA) and a project's proponent. The EPA should have a role in overseeing the pre-application consultation process by proponents, with rigorous oversight and the option of intervening.

Community feedback needs to be genuinely considered by the decision maker at each stage of the decision-making process. Both the project proponent and the new EPA must clearly explain how they have taken the community’s views into account.

When a decision maker gives notice to the proponent of a proposed decision and any conditions, there should be an opportunity for public comment. This is included in the current Act and should be retained – removing it weakens the law.

Without consultation at this stage of a proposed decision, community members do not get input on any conditions proposed, which may include things like offsets. Providing this opportunity is vital for transparency and community confidence.

Merits review

Community participation must not end with a project’s final decision. Our new laws must ensure that once a decision has been made, groups that care about the environment have the right to seek independent review of the merits of decisions, not just whether decisions followed the right process.

When decisions cannot be reviewed, it risks creating a decision-making culture of impunity with poor decisions for our threatened species.

Merits reviews will ensure the EPA rigorously and fearlessly assesses and decides on applications, based on the best available science. In doing so, it creates a culture of scientifically sound, well-bounded and justifiable decision making at the EPA.

5. Conservation planning

Key points

Our new laws must take environmental protection forward – not wind it back. That means:

- Make identifying and protecting critical habitat mandatory for every species.

- Retain current requirements in the Act to identify critical habitat and populations under particular pressure for threatened species and the actions required to protect them.

- Instead of weakening the current laws to a requirement not to act inconsistently with part of a Recovery Strategy and Threat Abatement Strategy – the new laws need to strengthen the current law to require compliance with the whole of Recovery Strategies and Threat Abatement Strategies.

- Clearly define “unacceptable impact” as including damage to critical habitat for threatened species and ecological communities.

More detail

Some key elements of the proposed reforms have the potential to deliver transformational change for threatened plants and animals.

But as it stands, these features are too weak, narrow and ambiguous to result in real change.

The proposed laws will introduce the term ‘unacceptable impacts’ to new project assessments.

Any project found to have unacceptable impacts on a protected matter will not be permitted under the new laws.

This is a welcome improvement with potential to deliver transformational change for our threatened species – it could deliver real on-ground protections for threatened species and their habitat from damaging projects.

Key concerns

But right now, the proposed definitions outlining unacceptable impacts are too narrow and ambiguous to deliver on the ground improvements for threatened plants and animals.

Recommendations

The definition of unacceptable impacts must be broadened to capture impacts ‘likely’ to occur – not just impacts that ‘will’ occur. Even the best available science can rarely predict future impacts with certainty. Setting such a high threshold for a project’s predicted impacts means any ‘likely’ unacceptable impacts – which often do eventuate in some form – could be permitted.

Currently, its proposed that an impact is unacceptable if it significantly reduces the ‘viability’ of a threatened species. How ‘viability’ is defined is crucial; it must clearly state this means species are not declining.

Damage to critical habitat must also be defined as an unacceptable impact.

Habitat is vital to the survival of threatened wildlife. Our new laws need to improve protections for critical habitat – not gut them.

Key concerns

The federal government has promised to turn around the extinction crisis, and to protect critical habitat, but the draft laws fall far short of this ambition.

In the draft laws, habitat protection areas are discretionary, and the concept of critical habitat has been abandoned.

In the proposed reforms, the vital legal concept of ‘critical habit’ has been abandoned, along with available legal protections for it. Critical habitat has clear legal meaning, has been applied on the ground, and is identified in recovery plans or draft plans for many species. It includes vital habitat for threatened species like areas necessary for breeding, maintaining genetic diversity and long-term evolutionary development, and species recovery. It has the best potential to protect important threatened species habitat on the ground, where it counts.

Protecting critical habitat needs to become mandatory, not be abandoned.

‘Critical habitat’ has been replaced with a new, vague definition: habitat that is both ‘irreplaceable’ and ‘necessary for survival in the wild’. These terms are ambiguous, with no known meaning, and have not been applied in practice. The Department has made clear that these new terms are intended together to capture less than habitat critical to the survival of species.

The consequences of this are concerning. For example, under this new definition, it’s unclear whether a 150-year-old hollow bearing tree, vital habitat for countless threatened animals, would be considered ‘irreplaceable’. It could be possible for a proponent to argue the tree is replaceable by substituting a nest box in its place, allowing an ancient tree providing endangered species habitat to be cut down.

Recommendations

The current legal definition of ‘critical habitat’ must be retained. If it is not, and the new terms are used to define unacceptable impacts, damage to either habitat that is irreplaceable or necessary for survival in the wild must be considered an unacceptable impact. If not, the reforms will reduce habitat protection for threatened species from the protections available in the current laws – taking protection of threatened species habitat backwards not forwards.

The new laws must make it mandatory to identify and protect critical habitat, using its current legal meaning, for every listed threatened species and ecological community.

The current EPBC Act has existing requirements to set out important, practical information in Recovery Plans, and that prohibit an action inconsistent with a Recovery Plan.

Key concerns

The reforms replace Recovery Plans with Recovery Strategies, but weaken the information required in them. The reforms also weaken the existing prohibition on actions inconsistent with a Recovery Plan, to prohibit only an action inconsistent with part of a Recovery Strategy, called a Protection Statement. But, the Minister can choose whether to make a Protection Statement or not, its not mandatory. Together, these issues take Conservation Planning backwards, not forwards, for our threatened species.

Recommendations

The reforms must maintain and strengthen the standard of information required in Recovery Strategies from requirements in the current Act, such as:

The reforms must maintain and strengthen the standard of information required in Recovery Strategies from requirements in the current Act, such as:

- the objectives to be achieved for the species (for example, removing a species or community from a list, or indefinite protection of existing populations of a species or community);

- criteria against which achievement of the objectives is to be measured (for example, a specified number and distribution of viable populations of a species or community, or the abatement of threats to a species or community); and

- specify the actions needed to achieve the objectives for the species; and

- identify the habitats that are critical to the survival of the species or community concerned and the actions needed to protect those habitats; and

- identify any populations of the species or community concerned that are under particular pressure of survival and the actions needed to protect those populations.

The reforms propose that Recovery Strategies will now be in 4 different documents.

The first document sets out threats to the species and is mandatory, but the other three documents that set out what has to be done to recover the species are discretionary – the Minister only needs to make one of these three documents.

The obligation not to approve actions that are inconsistent with Recovery Plans is weakened to a requirement not to approve an action that is inconsistent with ‘protection statements’ – one of the three discretionary documents. The same issues arise for Threat Abatement Strategies.

Together, these issues risk weakening recovery planning for our threatened species, instead of strengthening it.

The new laws should:

- Leave Recovery Strategies as a single document, to make sure everything that’s required for a species’ recovery is included, instead of risking some requirements being left out because of bureaucratic hurdles creating multiple documents for each species.

- At minimum, make Protection Statements mandatory for every species.

- Instead of weakening the current laws to a requirement not to act inconsistently with part of a Recovery Strategy and Threat Abatement Strategy – the new laws need to strengthen the current law to require compliance with the whole of Recovery Strategies and Threat Abatement Strategies.

- No removal of current requirements in the Act to identify critical habitat and populations under particular pressure for threatened species and the actions required to protect them, and other important practical information, within Recovery Strategies.

The reforms propose stricter protections for threatened species, migratory species and threatened ecosystems in the form of Critical Protection Areas. These new protection areas have the potential to deliver transformational improvements to our threatened species.

Key concerns

However, their identification is only optional. The Minister can choose whether to make a Critical Protection Area for a species, or not.

Similar optional protections have been available to government in Victorian law for more than 30 years – and have never been used, not once.

History tells us that habitat protections will only work for threatened species if they are mandatory, not optional.

Recommendations

Our new laws need to make it mandatory to identify and protect critical habitat, using its current meaning, for the 2212 ecological communities, plants and animals now at risk of extinction across Australia.

Critical habitat should always be protected in a Critical Protection Area.

Further, the new National Environmental Standards should prohibit damage to critical habitat, and not permit it to be offset.

6. Environment Information Australia

Key points

Australia’s new laws must mandate that:

- Decision making is based on the best available scientific data.

- Data must be available to the community.

- Robust data collected by experts and citizen scientists must be given equal weight to other relevant pieces of evidence.

More detail

Environment Information Australia is a new body that will store and collate environmental data for use by proponents and the EPA in assessing environmental impacts.

Its establishment is a welcome reform that can help ensure the new Act delivers environmental decision-making firmly based on science, instead of politics.

A key recommendation from the independent review of Australia’s national environment laws is to ensure all environmental decision making requires the use of the best available science. This requirement is missing from the proposed new laws and should be delivered as a requirement in the new National Environmental Standards, and in the Act.

Critically, data collected by experts and citizen scientists that is well documented and with good evidence should be given equal weight to other relevant pieces of evidence – regardless of whether citizen scientists conducted this research with permission to access a site. Whether or not an expert or citizen scientist had permission to enter a site does not necessarily impact the veracity of any observations made, and therefore should not be a relevant consideration for using data.

What matters is that the data is robust and well-evidenced; it’s inappropriate to exclude good data based on whether somebody was allowed to collect it, and doing so has the effect of bias in favour of proponent-owned data.

7. Environment Protection Australia

Key points

By law, Australia’s new federal EPA must:

- Be able to independently and fearlessly assess impacts on the environment using the best available science.

- Act without political interference or Ministerial “call in” powers.

- Be properly resourced and empowered to assess environmental impacts.

More detail

The federal government has already committed to introducing a new, federal environment authority – Environment Protection Australia.

This is a welcome step forward that can move us away from environmental decision-making based on politics and towards decisions based firmly on independent scientific assessment.

The federal EPA must be set up to succeed. It should be established as a trusted decision-maker that monitors compliance, conducts inspections, investigations and assessments, makes rigorous and independent decisions aimed at halting decline and recovering our threatened species, and takes legal action against people or companies that damage our environment.

The new EPA needs safeguards built-in to protect its independence, resources, and staff to match its ambitions.

To genuinely safeguard this powerful new position from political interference, the EPA’s CEO must be accountable to an independent board with qualified members. The board must by supported by clear governance and reporting requirements.

The independence and authority of the EPA must not be undermined by the inclusion of broad Ministerial ‘call-in’ powers in our new environment laws. These powers would create an alternative back-door approval pathway, which could be subject to inappropriate political influence and corruption. Worryingly, once a decision is called-in by the Minister, there are no longer requirements for the action not to have unacceptable impacts and not to be inconsistent with the National Environmental Standards, Recovery Strategies and Threat Abatement Strategies.

Our new laws must also outline a rigorous assessment process, in which the new EPA can independently and fearlessly, using the best available science and with full community-confidence and integrity, assess the environmental impacts of a proposal. Currently, project proponents are allowed to conduct their own environmental assessments – resulting in environmental decision-making that too often benefits proponents over the environment.

The EPA must be resourced and empowered to carry out environmental impact assessments, to put an end to a system stacked against the environment from the start.

8. Environmental assessments and approvals

Key points

Australia’s current environment assessment and approval processes are broken and full of holes.

Our new laws must require rigorous, science-based decision making, not give decision makers god-like discretionary powers that are vulnerable to influence.

Under our new laws, decisions must:

- Be objective – based on science and clear rules, not subjective – based on what a decision-maker might think and vague terms.

- Remove discretion – removing all references to decisions made ‘to the satisfaction of’ the EPA CEO or the Minister, because it makes decisions subjective instead of firmly based on science.

- Require actions to comply with all content in Recovery Strategies and Threat Abatement Strategies – not parts of those, and not to a weaker standard of ‘not inconsistent with.’

- Apply the best-available science and consider cumulative impacts.

- Be made within a fair and realistic time for EPA to thoroughly assess impacts applying independent data, not just rubber-stamp proponent’s self-assessments.

- Not be permitted on the basis that cost-effectiveness is more important than protecting nature.

More detail

The draft reforms continue to give decision makers wide personal discretion when deciding whether projects will cause too much harm thousands of plants, animals and places across Australia – with little transparency or accountability.

This leaves major decisions on everything from land clearing to mining to renewable energy subject to the whim of the decision maker of the day.

It is vital our new laws require effective, robust and fair processes. Excessive decision-maker discretion must be removed, so that a rules-based, science-backed system can replace it – and actually deliver good outcomes for nature.

Establishing a rules-based system that requires compliance with clear rules and outcomes for our environment, especially threatened species, was a key recommendation of an independent review of the EPBC Act.

There are eight key improvements that must be made to fix environmental assessment and approvals in the draft environment laws.

The current draft laws embed decision-maker discretion and subjectivity, leaving too much space for political interference and arbitrary decisions. This kind of language needs to go to deliver on the promise to move from a discretionary system to a rules-based system.

Instead of requiring all decisions about whether environmental impacts are unacceptable and comply with the Standards to be grounded in facts and the best-available science, the Albanese government’s draft laws make these subjective decisions that “satisfy” the EPA’s CEO. This enables poor decision-making, with decisions based on what the EPA’s CEO ‘thinks’ about impacts on the environment – rather than what the science says.

This kind of decision-maker discretion has been a key failure of our current environmental laws, allowing approvals of projects with unacceptable environmental impacts at odds with what the science says is required to protect threatened species.

To improve outcomes for threatened species, decisions about unacceptable impacts on the environment must be objective, based on the best available science.

- Objective tests ensure rigorous decision-making.

- If the science shows impacts are likely to be unacceptable for the environment, or that a project is likely to break National Environmental Standards, the project should not be permitted.

- Legal loopholes, like whether the decision-maker is ‘satisfied’, need to go.

The new laws need to create clear rules that won’t allow bad decisions for our environment, no matter what.

Under our new laws, actions, environmental assessments and approvals must be compliant with National Environmental Standards, and all Recovery Strategies and Threat Abatement Strategies – in full, not just in part.

The proposed reforms require decisions or projects to be ‘not inconsistent with’ the National Environmental Stands, Recovery Strategies and Threat Abatement Strategies.

This framing weakens the quality of decisions; our laws must go further and require compliance with each of these standards.

This fundamental principle of environmental law is required for decision-making under the current Act – it should be elevated to a principle with which actions and decisions must comply, not just consider.

New laws must not go backwards. Some parts of the proposed laws weaken important aspects of the current assessment process.

Key elements of current processes that must remain include:

- Proponents must continue to be obligated to apply for approval if they think their project may or will have a significance impact on MNES. This critical obligation cannot be weakened to a discretion, as in the proposed reforms.

- The option of assessment by public inquiry should remain, because it is suitable for particularly controversial or complex projects.

- Regulators must continue to be required to provide proponents with guidelines on how to conduct their impact assessment. Tailored guidelines may be provided to suit specific projects.

- Actions that may have significant environmental impacts should be required to go through a proper assessment, not waved through without adequate assessment under a proposed new low-impact pathway. Only projects with no significant environmental impacts are suitable for low-impact pathway approval.

For Australia’s new environment laws to work properly, approval decisions must factor in additional mandatory considerations. This should apply for both proposed pathways – low-impact and standard.

These additional mandatory considerations should include:

- Best available science relevant to the action, any adverse impacts that may occur, and the protected matters for which the action is regulated. This was recommended in the Samuel Review and should be delivered because it helps ensure decisions that are most likely to improve threatened species’ outlook.

- Considerations of cumulative impacts, based on best available science. While an individual project may not have a disastrous impact for the environment, collectively, multiple projects can, and do, cause significant harm. Assessments must consider cumulative impacts rather than assessing projects in isolation. Assessing cumulative impacts is a particularly crucial role of the new EPA; individual project proponents do not have the ability to assess cumulative impacts, but the EPA, in a critical oversight role, can and must do this.

- The Objects of the Act. This is to ensure decision-making aligns with the Act’s purpose, including to halt and reverse declines. The object of halting and reversing decline of threatened species should be an express object of the Act. Our new laws need to aim to achieve this, and say so.

The amount of time the EPA has to assess project applications must be increased. Under proposed reforms, decision timeframes are vastly insufficient to allow for rigorous assessment.

- For ‘low-impact’ pathway applications, where the applicant does not believe their proposal will have significant impacts on the environment, the proposed timeframe is 2 weeks.

- For ‘standard’ pathway applications, where the applicant believes their project may or will have a significant impact, the proposed timeframe is 60 days for the EPA to conduct its assessment and determine any required conditions. Currently, assessment and approval more many projects takes more than 3 years.

More time must be built into the system to make sure the EPA has the time it needs to properly scrutinise applications, identify environmental impacts and review these impacts against National Environmental Standards and any listed unacceptable actions, consider any species’ recovery and threat abatement plans, decide on the application and determine any required conditions.

The draft laws include a proposal that conditions on a project should be a cost-effective means to achieve their object.

This requirement for cost-effectiveness must be removed.

If included, this requirement could mean expensive conditions that are necessary to achieve crucial environmental outcomes will not be applied. In reality, for high impact projects, protecting threatened species will be expensive – an expense which is necessary and justified if high risk projects are to go ahead.

Our new laws must retain and strengthen current requirements in the Act to consider up-to-date information. These requirements exist in some form under current laws, such as via applications for reconsideration of an approval, and powers of suspension, revocation and variation.

But the current powers are too weak and narrow. For example, by failing to require consideration of species newly listed as threatened, or placed in a higher threat category, after applications for development are made, but before approval is granted.

Broad restrictions preventing new species listing events from being considered hinder the effective protection of threatened species, and current restrictions must be removed not replicated in the new laws.

Decisions within application processes must consider all current listings of threatened species and up-to-date information.

9. Regional planning or strategic assessments

Key points

Australia’s new laws must be built around robust and comprehensive assessment – not blanket approvals and corner cutting. This means:

- All individual actions require individual assessments under the new laws.

- No exemptions for ‘classes’ of actions, like logging.

- Not permitting offsets or payments as replacements for genuine environmental protection

More detail

The federal government’s proposed laws introduce a regional planning structure. Regional planning involves pre-identifying areas within a region as areas for environmental protection, or areas for development.

Any regional planning needs to deliver on the Government’s promise in the Nature Positive Plan to protect all critical habitat – as the term is currently defined. Critical habitat must be identified in Recovery Strategies for every threatened species, to achieve this.

Under the federal government’s proposed plans, thorough assessment of individual projects could be replaced by assessment for ‘classes’ of actions. These classes could then receive assessment exemptions – which we’ve seen with native forest logging under the current EPBC Act. It’s critical that all individual actions require individual assessments under the new laws.

The proposed laws, in removing assessment requirements for certain classes of actions, appear to switch this requirement off in exchange for offsets, which would be required under other aspects of the reforms anyway. But, under regional plans, offsets could become generic, diffuse environmental projects, instead of being targeted at the species impacted by a particular project.

Requirements for environmental protection could be replaced with ‘net positive outcomes’ – allowing proponents to buy their way out of environmental protection with no requirement for offsets to be identified as available, put in place before the damage occurs, nor for the offset project to even be directed to the same species. This scheme risks doing nothing to properly protect the environment – while allowing destruction of nationally important parts of our environment.

Any introduction of a new regional planning system must:

- comprehensively protect environmental values, including all critical habitat

- be capable of accommodating new information about risks and what needs to be protected in a timely manner

- actively seek to identify areas that may be suitable for national heritage, world heritage or Ramsar wetland site nomination

- not allow for exemptions for specific sectors – such as native forest logging

- not allow for reduced or streamlined approval processes in areas where there may be significant impacts on MNES

- not allow for payments for destruction or weaker offsets, without strict requirements.

10. Other: First Nations Rights

Key points

First Nations must be meaningfully involved in decisions that impact their Country and culture.

Australia's new environment new laws should:

- Grant First Nations people a key legal role in decision making, with guaranteed free, prior and informed consent.

- Ensure legal rights for First Nations to protect, care for and manage Country and culture, and rights outlined by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

More detail

To create a better future for everyone, our new nature laws must truly value the rights, knowledge and culture of First Nations people.

First Nations people must have a key role in decision making, with guaranteed free, prior and informed consent. They must have legal rights to protect, care for and manage Country and culture, rights outlined by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

First Nations aspirations to protect and manage culturally significant species must be delivered in the reforms.

10. Other – Offsets

Key points

No one should be allowed to buy their way out of environmental protection. Australia’s new laws must:

- Not permit financial offsets, termed ‘restoration contributions.’

- Only permit offset projects in strictly limited circumstances, in line with the best available science.

- Recognise not everything can be offset; damage to critical habitat, World Heritage and National Heritage cannot be made good by a project elsewhere, and red lines must be drawn.

More detail

Proposed reforms could see project proponents able to make payments instead of project-specific offsets – meaning they could buy their way out of protecting the environment.

If allowed, these payments are likely contribute to the extinction of some threatened species, ecological communities and migratory species. In NSW, the Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal recently recommended that the option of payment into a Fund should be phased out of the NSW Biodiversity Offsets Scheme (December 2023).

The reform proposal for “Restoration Contributions” is a clear backwards step from the current EPBC Offsets Policy, that is likely, if adopted, to facilitate the extinction of some threatened species, ecological communities and migratory species.

The reforms cannot take us backwards by weakening limitations on the use of offsets from how they are applied under the current Act. Instead, use of offsets needs to be minimised further, with strict rules applied to their use.

Other forms of offsetting should only be allowed in limited circumstances, in line with the best available science. This is because offsetting rarely leads to achieving good biodiversity outcomes. The EPA should be required to identify that the necessary offset for a protected matter can actually be delivered before determining whether an offset will be permitted.

The proposed reforms feature some improvements to offsetting as it currently occurs under the EPBC Act. These include requirements for like-for-like direct offsets, reducing use of averted loss offsets, making sure that offsets are deliverable, requiring offset actions to have demonstrably commenced prior to the impact occurring, are significant improvements over current offsets under the Act.

But our new laws must recognise not everything can be offset – some of our plants and animals are simply too precious and rare to be traded-off. This includes critical habitat for all threatened species, all World Heritage places and National Heritage places.

Further improvements to offsetting under new laws must:

- Limit time lag to benefits from the offset.

- Require the end condition or quality of the offset site to be at least as high as the impact site.

Require offsets to be in biologically meaningful areas and delivered in biologically meaningful timeframes.